Fictional television shows, such as Prison Break, Oz, and Orange is the New Black, have helped bring criminal justice concerns to the popular mind.

For instance, fans or casual viewers of these TV series may have seen how mass incarceration and related problems can negatively impact inmates’ rehabilitation progress.

Sure, dramatic concerns make some of the situations in these programs appear overstated. That said, a quick survey of the United States (U.S.) criminal justice system shows that inmates and the public issues arising from prison population growth are real.

What is the overall number of prisoners and jail inmates in the U.S., and how does it differ from other countries? Also, what are the contributing factors to the high rates of incarceration, and how does it impact the community and individuals?

LookUpInmate.org provides essential information regarding incarcerated people, state prisons, and county jails across the U.S.

This article presents the latest data regarding the number of incarcerated people in the U.S., including demographic changes.

Learn what these statistics mean for the criminal justice system and those under its governance, including detainees and jail and prison inmates.

U.S. Has World’s Highest Incarceration Rate

If you work for an advocacy group, you likely already know that the U.S. has the highest rate of incarceration worldwide.

But another interesting fact regarding this issue is that every U.S. state incarcerates more individuals per capita than virtually any other democratic nation on Earth.

States like Massachusetts and New York may have lower incarceration rates than Texas, Louisiana, Illinois, and Mississippi. However, on a state level, every U.S. state remains overly dependent on prisons and jails as tools of the criminal justice system compared to the rest of the world.

How Many People Are Incarcerated in the U.S.?

The U.S. prison population was 1,204,300 by the end of 2021, a 1% drop from 2020 (1,221,200) and a 25% decline from 2011 (1,599,000).

What You Need to Know

Here are three crucial facts regarding mass incarceration in the U.S.:

- The U.S. spends over $80 billion on incarceration annually.

- Blacks serve time for drug offenses at a rate 10 times higher than Whites, even though both use drugs at similar rates.

- State, local, and federal governments spend between $20,000 to $50,000 annually to confine people behind bars.

What Percentage of the U.S. Population Is Incarcerated?

About one out of every 100 U.S. citizens serves time in a corrections facility, meaning approximately 0.7% of the country’s population is in a federal or state prison or local jail.

National Rates Mask Regional Variations

Overall imprisonment rates may appear reduced on official reports. However, people should remember that regions may vary regarding incarceration statistics.

National rates often ignore regional differences regarding this concern. For example, the incarceration rate in Washington, D.C. (an urban area) and a rural county in Maine will likely differ significantly.

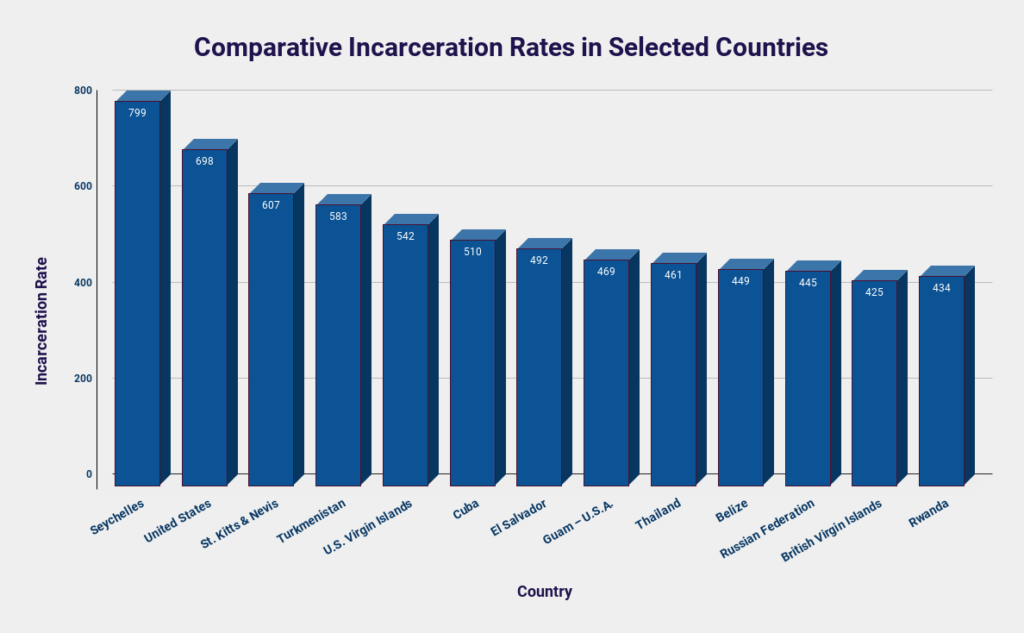

Incarceration Rates in Selected Countries

Here are the incarceration rates for thirteen countries, highlighting those with the highest prison population rates. The data given show the number of prisoners for every 100,000 of the national population.

- Seychelles: 799

- United States: 698

- St. Kitts & Nevis: 607

- Turkmenistan: 583

- U.S. Virgin Islands: 542

- Cuba: 510

- El Salvador: 492

- Guam – U.S.A.: 469

- Thailand: 461

- Belize: 449

- Russian Federation: 445

- British Virgin Islands: 425

- Rwanda: 434

Homicides in the U.S.

The number of convicted homicide offenders serving time in BOP (Bureau of Prisons) or private-run correctional facilities is 2,426, approximately 1.7% of the nation’s prison population.

Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie

As public demand for criminal justice reform continues to grow — and as global crises like the pandemic heighten the stakes — getting the incarceration facts straight is more critical than ever.

The U.S. does not have a single criminal justice system. Instead, the nation has thousands of local, state, federal, and tribal systems.

- 3,116 local jails

- 1,566 state prisons

- 1,323 juvenile correctional facilities

- 181 immigration detention facilities

- 80 Indian country jails

- 98 federal prisons

- Civil commitment centers

- State psychiatric hospitals

- Military prisons

Prison Population Over Time

Some estimates say that around two million people are in the nation’s jails and prisons, a 500% spike over the past 40 years.

Laws and policies on sentencing, rather than crime rates, are likely the reason behind this increase. These trends have contributed to prison overcrowding and become a burden on the national and state budget.

Unfortunately, despite indications that large-scale incarceration is ineffective in achieving public safety, the justice system continues to accommodate rather than mitigate a rapidly expanding penal system.

Lessons From the Smaller “Slices”: Immigration, Youth, and Involuntary Commitment

The U.S. has approximately 47,000 youth in confinement, with many imprisoned for offenses that are not crimes, like non-criminal probation violations, and status offenses like running away or truancy (skipping school without good reason).

In addition, approximately 1 in 16 youth held for delinquent or criminal offenses go to adult correctional facilities, while others are in juvenile detention centers that resemble prisons.

Furthermore, nearly 6,000 people spend time in federal prisons for criminal convictions related to immigration, with the majority charged with illegal entry or reentry, a less serious offense than crossing the border undocumented.

Additionally, 22,000 people are involuntarily detained in state psychiatric hospitals and civil commitment centers.

Beyond the “Whole Pie”: Poverty, Community Supervision, and Race and Gender Disparities

Beyond the “whole pie” of mass incarceration, it is crucial to consider the vast number of people affected by the criminal justice system.

Aside from the incarcerated population, 803,000 people are on parole, and 2.9 million are on probation.

Meanwhile, criminal records and prison sentences often result in poverty, dissolving wealth, creating debt, and negatively impacting employment opportunities. Poverty can be a predictor or outcome of incarceration.

Gender and Racial Disparities in Mass Incarceration

Racial disparities exist in the nation’s prisons and jails, with people of color, especially Black Americans, significantly overrepresented.

Black Americans constitute 38% of the incarcerated population despite making up only 12% of U.S. residents.

Meanwhile, women’s incarceration rates have risen faster than men’s due to financial difficulties like the inability to pay bail.

Policymakers seeking incarceration reform may also consider these factors indicating disparities:

- Between 2020 and 2021, the imprisonment rate of Black adults in the U.S. decreased by 4% (from 1,238 to 1,186 per 100,000), while the imprisonment rate of Hispanic adults dropped by 3%.

- The imprisonment rate for all female U.S. residents in 2021 was 47 per 100,000, approximately one-tenth that of all male U.S. residents, who had a rate of 659 per 100,000.

- Among all racial or ethnic groups, Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Other Pacific Islanders had the lowest incarceration rates, with 90 prisoners per 100,000 adults and 72 prisoners per 100,000 of all ages.

A Large Number of Black Prisoners

As of 2022, Black people went to jail at a rate four times higher than White people and spent 12 more days behind bars on average across the 595-jail sample, contributing significantly to the increase in population observed for Black individuals.

The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit reform advocacy group, suggests that Black Americans (or African Americans) are incarcerated in state prisons nearly five times as often as white Americans. Meanwhile, Latino Americans are imprisoned at 1.3 times the rate of White Americans.

America’s Incarceration Rate Falls to Lowest Level Since 1995

The nation’s incarceration rate reached 1,000 inmates per 100,000 adults between 2006 and 2008. Since then, the rate has decreased steadily and, by yearend of 2019, was at the same level as in 1995.

What Actually Happened to Jail and Prison Populations During the Pandemic?

During the first year of the pandemic, there was a significant reduction in incarcerated populations: the number of people in prisons fell by 15% in 2020, and jail populations dropped even faster, down 25% by the summer of 2020.

Jails vs. Prisons: What’s the Difference?

Inmates under the custody of a state, federal, or local correctional authority typically reside in a local jail or a state or federal prison.

Jails hold people before or after adjudication and are generally run by law enforcement authorities such as a police chief, a county administrator, or a sheriff.

On the other hand, prisons confine people after they have been convicted of a crime and are usually subject to the state’s Department of Corrections (DOC) or the national government’s Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP).

Eight Myths About Mass Incarceration

The “war on drugs” policy, the use of private prisons, and low-paid or unpaid prison work remain controversial issues in criminal justice today.

Focusing on the policy reforms that can end mass incarceration, not just curb it, requires the public to consider these issues.

The First Myth: Private Prisons Are the Corrupt Heart or Primary Cause of Mass Incarceration

The vast majority of incarcerated people are in publicly-owned prisons and jails.

Although some states have more private prisons than others, and the industry has lobbied to maintain high levels of incarceration, private prisons are essentially parasites on the massive publicly-owned system, not its source.

The Second Myth: Prisons Are “Factories Behind Fences” That Exist to Provide Companies With a Huge Slave Labor Force

Private companies that use prison labor do not stand in the way of ending mass incarceration, nor are they the causes of most prison employment.

Most work for state-owned “correctional industries,” which pay much less than private companies but only represent about 6% of all people incarcerated in state prisons.

Prisons pay incarcerated people unfairly low wages for food service, laundry, and other operations.

The Third Myth: Releasing “Nonviolent Drug Offenders” to the Society Would End Mass Incarceration

Drug offenses contribute to the imprisonment of more than 350,000 people, and drug convictions remain a defining characteristic of the federal prison system.

That said, four out of five people in jail or prison are there for a crime other than a drug offense.

Society and the criminal justice system should change how they respond to crimes more serious than drug possession to end mass incarceration.

The Fourth Myth: By Definition, a “Violent Crime” Involves Physical Harm

When discussing crime-related topics, people often use the terms “violent” and “nonviolent” as shorthand for serious versus nonserious criminal offenses.

Unfortunately, these terms are also coded (often racialized) language to label groups of people (races or ethnicities) as inherently dangerous versus non-dangerous.

In reality, federal and state laws use the term “violent” for a wide array of crimes, including many that do not cause bodily harm.

For example, some states may categorize purse snatching, producing methamphetamine, and stealing drugs as violent crimes.

The Fifth Myth: People in Prison or Jail for Violent or Sexual Crimes Are Unsafe or Dangerous to Be Released

This assumption reflects the false belief that people who commit violent or sexual crimes are beyond rehabilitation and deserve many decades or even lifetimes in prison.

However, recidivism data (information regarding reoffense) do not support the notion that violent crime victims should be detained for decades to ensure public safety.

For example, people convicted of sexual or violent offenses are among the least likely to be rearrested.

Also, those convicted of sexual assault or rape have rearrest rates 20% less than other offense categories combined.

The Sixth Myth: Crime Victims Want and Support Long Prison or Jail Sentences

Policymakers, prosecutors, and judges usually invoke victims’ names to argue for long sentences for violent offenses. However, contrary to the popular view, most victims of violence prefer violence prevention programs, not imprisonment.

By a more than two-to-one margin, victims favor crime prevention, crisis intervention, and strong communities over increased arrests, strict penalties, and incarceration.

The Seventh Myth: Some People Need to Go to Jail or Prison to Get Treatment and Services

People caught up in the criminal legal system often have unmet needs. Still, prisons and jails are not ideal for recovering from a mental health problem or substance use disorder.

For example, local jails may be filled with people requiring medical care and social services. However, these facilities usually lack the resources to provide them.

The Eighth Myth: Expanding Community Supervision Programs Is the Most Effective or Best Way to Reduce the Rate of Incarceration

Community supervision, such as parole, probation, and pretrial supervision, is considered a lenient penalty or an ideal alternative to imprisonment.

But while living in the community is preferable to being locked away, the supervision requirements can be so restrictive that they make it hard for former inmates to succeed.

Offense Categories Might Not Mean What You Think

The reported offense data often oversimplifies incarceration’s primary causes in two ways:

- The data only shows the most serious offense when someone is behind bars for multiple offenses, underplaying the complexity of criminal behavior.

- The report often groups people convicted of various offenses under a single category, misrepresenting and exaggerating the extent of violent crime.

For instance, the label “murder” typically includes various situations and parties, from serial killers to acts that are unlikely to occur again or did not directly cause death under existing felony murder statutes.

This lack of nuance could blur significant details about persons’ involvement in the criminal justice system and their actual offenses.

Recidivism: A Slippery Statistic

While policymakers mention reducing recidivism frequently, few states collect the data that allows them to measure and optimize performance in real-time.

For instance, the Council of State Governments inquired about the recidivism statistics correctional facilities collect and publish for individuals leaving prison and entering probation.

The organization observed that states usually track only one measure of post-release recidivism, and only a few track recidivism while on probation.

The Impact and Cost of Mass Incarceration

Many proponents of incarceration argue that putting individuals behind bars reduces crime. However, studies have shown the opposite to be true.

For example, a 2015 study reported that since 2010 the increased incarceration rate accounted for nearly 0% of total crime reduction.

Incarceration can also be expensive. A Vera Institute of Justice study showed that the U.S. budget expenditure on incarceration was roughly $33 billion in 2000 for an equivalent level of public safety the country achieved in 1975 for $7.4 billion (about 25% of the current cost).

The High Costs of Low-Level Offenses

Many justice-involved individuals in the U.S. do not face serious charges. They are often cited for misdemeanors or minor offenses.

Still, even low-level offenses, like technical parole and probation violations, can result in incarceration and damaging consequences.

Cities and counties spend significant amounts of public resources handling and punishing these minor offenses rather than investing in community-driven safety measures.

Probation and Parole Violation “Holds” Lead to Unnecessary Incarceration

Over the past few decades, arbitrary and excessive supervision regimes have pushed people back into prisons and jails, resulting in mass incarceration.

The DOJ’s (Department of Justice‘s) Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) noted that 16 percent of U.S. prison admissions in the late 1970s resulted from parole and probation violations.

This percentage reached a record of 36% in 2008. In 2018, the latest data available was 28%.

Misdemeanors: Minor Offenses With Major Consequences

An estimated 13 million people face misdemeanor charges, such as jaywalking or sitting on the sidewalk, sending millions of Americans into the criminal justice system yearly (excluding civil violations and speeding).

These low-level offenses typically comprise 25% of the daily jail population nationally. These numbers are also much higher in some states and counties.

“Low-Level Fugitives”: Former Inmates Live in Fear of Incarceration for Unpaid Fines and Missed Court Dates

Defendants can end up behind bars even if their crimes are not punishable by jail time.

For instance, if a defendant misses court appearances or has to pay a fine or payment, the judge issues a “bench warrant,” authorizing law enforcement to hold them until court proceedings can be conducted.

What’s at Stake

Despite making up nearly 5% of the world population, the U.S. accounts for 20% of the global prison population.

Since 1970, the country’s incarcerated population has grown by 500%, resulting in about 2 million people incarcerated today, surpassing population growth and crime.

The prison system costs taxpayers at least billions of dollars per year. The money could have been spent on building communities rather than harming them. Improving safety requires investments in rehabilitation programs.

If you’re looking to further your studies regarding mass incarceration, you can visit official government websites, such as the following:

- The U.S. Census Bureau: https://www.census.gov/

- Bureau of Justice Statistics: https://bjs.ojp.gov/

References

- States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2021.html - Prisoners in 2021 – Statistical Tables

https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2021-statistical-tables - Fight for Smart Justice

https://www.aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/mass-incarceration - “What percent of the U.S. is incarcerated?” (And other ways to measure mass incarceration)

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/01/16/percent-incarcerated/ - World Prison Population List

https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf - Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html - Growth in Mass Incarceration

https://www.sentencingproject.org/research/ - Racial Disparities Persist in Many U.S. Jails: Despite narrowed gap in incarceration rates, Black people remain overrepresented in jail populations, admissions—and stay longer on average

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2023/05/racial-disparities-persist-in-many-us-jails - The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons

https://www.sentencingproject.org/app/uploads/2022/08/The-Color-of-Justice-Racial-and-Ethnic-Disparity-in-State-Prisons.pdf - America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995/ - Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 34 States in 2012: A 5-Year Follow-Up Period (2012–2017)

https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/rpr34s125yfup1217.pdf - BJS fuels myths about sex offense recidivism, contradicting its own new data

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/06/06/sexoffenses/ - National Survey of Victims’ Views on Safety and Justice

https://allianceforsafetyandjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Alliance-for-Safety-and-Justice-Crime-Survivors-Speak-September-2022.pdf - Use data to drive recidivism-reduction efforts

https://50statespublicsafety.us/part-2/strategy-1/ - What Caused the Crime Decline?

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/what-caused-crime-decline - The Prison Paradox

https://www.vera.org/publications/for-the-record-prison-paradox-incarceration-not-safer - Revoked

https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/31/revoked/how-probation-and-parole-feed-mass-incarceration-united-states